MBP: Startup M&A Bidding Wars

Founders beware, bidding wars are to be handled with care!

If you haven’t already - get the second edition of the MBP book here. This all makes a lot more sense if you’ve read the book!

The prevailing wisdom in startup M&A is that the best way to maximize price is to drive competition. The holy grail being a bidding war between aggressive acquirers. That you should design your startup M&A strategy with the ultimate objective of creating a highly competitive field of potential acquirers. Talk to virtually any investment banker, and many board members, they will immediately default to “competitive process” as the driving force in startup M&A valuation.

Bidding wars happen, and in some cases they can enhance an outcome. But be careful if you’re designing a strategy that has as its singular focus a culmination in a bidding war.

The MBP posits that you might in fact be the casualty in a bidding war. I’d argue that a bidding war is at best a fortunate byproduct of a well executed strategy, and at worst a bad idea.

Let’s unpack why.

PBI size and strength

As it says in the MBP book valuation is derived from the unique utility of your startup to each particular buyer. Each buyer-seller pairing has its own valuation profile. This is because the partner big idea (“PBI”) powering the acquisition is going to be different from buyer to buyer. One PBI may be massive in scale, while another may be much more modest.

In the MBP.co post MBP New Gap Chapter 5.5: PSP liftoff I introduced the Big Idea Landscape concept. Where we think of the PBI in terms of boxes on a grid. Let’s employ this grid again, but this time in the context of bidding wars.

The Big Idea Landscape frames the PBI within the major market forces creating the opportunity for the potential strategic partner (“PSP”) and your startup.

There are 100 boxes, but only 7 filled in. The PSP has 6 elements of the big idea and your startup has 1. The 97 other boxes are the gold. It's in these boxes that together you’re going to build the partner big idea.

You want the PBI to be big, and for your startup to be at the center of it. The PBI is represented by the purple boxes (purple being a blend of your red box and their blue boxes). You are in the middle of the action - you are the key box that unlocks the other boxes. One box to rule them all, my precious.

You want your valuation to be a function of the potential of the purple boxes - not simply the intrinsic value of your red box. You want to be valued on what the PBI will be, not what your startup is today.

Let’s add one more dimension to the purpleness of the PBI boxes, shade. The darker the boxes the greater the commitment that the PSP has to the PBI.

Lots of factors go into commitment. As we saw in the MBP.co post on the Waze acquisition the deal with Buyer A fell apart because it came to pass that the acquisition thesis wasn’t as clear as everyone had hoped, the teams didn’t click, and there was a lack of executive leadership for the PBI. The PBI covered a lot of boxes, but it was in a light shade of purple.

PBI scenarios

Let’s plot a few PBIs at various levels of maturity (and an update from the original post - and per a great question from Marty McMahon - in reality the blue boxes would be in different locations and different number from PSP to PSP - but to keep things simple I’m keeping them in the same spot).

Potentially giant PBI but still very early in its formation (light shade):

Modest PBI that’s starting to gain some traction in the organization (shade getting darker):

Medium sized PBI taking hold in the organization, on the verge of getting serious (shade is almost dark):

Pretty small PBI, but they are ready to roll, all in (doesn’t get more purple than that)!

Understanding PBI size, shape, and shade

Most PSPs are large, distributed, organizations and getting alignment on even relatively small decisions takes time. Now imagine the kind of time it takes to align on a massive new strategy, in a brand new arena.

Remember it’s not just a small decision about acquiring your red box, it’s a much bigger decision about entering all the purple boxes. In the MBP book I dive into the process of developing PBIs, but the complexity doesn’t stop with just the development of the PBI. The PBI exists in the PSP’s organizational context. To execute the PBI the PSP is going to need a mountain of organizational alignment. Just a short list aligning elements: corporate objectives, product strategy, economics, regulations and compliance, operations, cultural, deal team capacity, executive sponsorship, and business unit leadership. The fewer of the key elements aligned at the PSP, the lighter the shade of purple.

Further, it’s risky to think that pressure from the startup is going to coalesce the PBI and darken the shade of purple. More often than not startup pressure is going to cause the PBI to fade away.

The other problem is that if you’re not working closely with a given PSP you don’t know the real shape and size of their PBI, let alone its shade. If we look again at Waze’s first (failed) run with Buyer A, we see that they jumped into deal mode while the PBI’s shade was still pretty light - resulting in a failed deal. There’s an argument to be made that moving that process more slowly, deeply understanding the nature of the PBI, and the level of commitment Buyer A actually had to it, before diving into deal-mode would have been a better plan.

Moving thoughtfully through the PBI build-up process will give you a much clearer understanding of the size, shape, and most importantly, the shade of each PSP’s PBI. This participation in the PBI creation process will enable you to do everything you can to develop the biggest PBI possible, while also giving you critical visibility into the PSP’s position. Don’t fly blind!

Bidding war gone wild

You’ve known PSP 1 for years. With them you’ve developed a deep understanding of a powerful PBI. You get a call from the general manager of the division you’ve been working with and you can tell she’s feeling out your interest in potentially being acquired. You know she’s excited about the strategy.

Let’s say this PSP 1’s PBI grid looks like the following:

You have a pretty good sense of the general size and shape of the PBI, and you know it’s beginning to take hold at PSP 1. They aren’t all in on the PBI yet, but it’s getting there. You call a board meeting and several of your board members think now could be a good time to be acquired. Further they think if PSP 1 might be interested then it must be the case that PSP 2, PSP 3, and even PSP 4 would also jump on this opportunity. They bring in an investment banker who tells them the best way to get the top price is to get your startup prepared, reach out to the premier buyers, run a competitive auction, and leverage the resulting competition to reach the max valuation. The banker is hired on the spot.

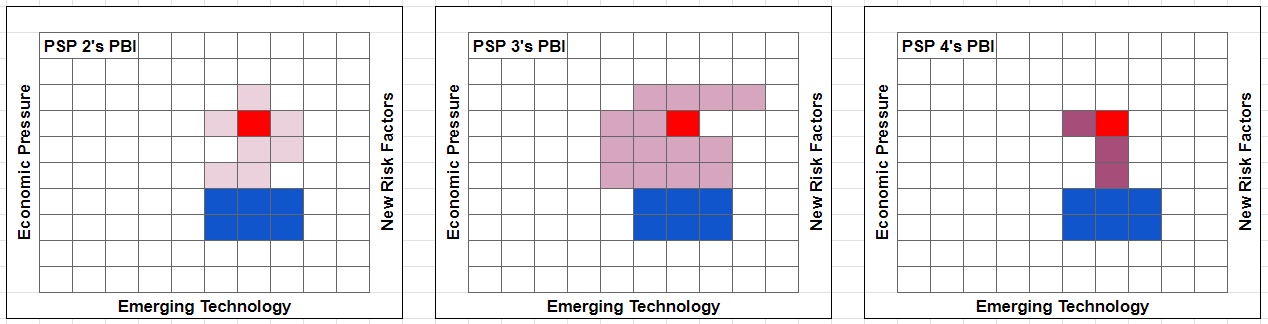

You don’t know these other PSPs nearly as well as PSP 1, and they don’t know you. They are, however, familiar with your general arena, and PSPs hate to lose out on an opportunity that might benefit a competitor, so they all jump in to take a look. Given this is all moving pretty fast it’s hard for you to know exactly the contours of their PBIs, but in reality here’s how things look on their side of the table:

PSP 2 is just too early in their thinking and they quickly decide to pass on the opportunity to acquire your startup. PSP 3 is talking about a pretty big opportunity and they are energized by the scale of the potential. They want to stay in the game and communicate that they are very interested and will be competitive from a valuation standpoint. PSP 4 has been working on a similar strategy for months and it so happens you would fit perfectly into it! They are in also! The banker is pumped and reports back that PSP 3 and 4 are in the game.

PSP 1 is a bit annoyed that what started as a genuine exploration has turned into a mele. But they also understand that business is business and they make their offer. PSP 3 isn’t sure if this is exactly the right time, but since they’ve figured out the PSP 1 is in the game they decide to play a bit longer and make their offer. PSP 4 loves this idea and makes their offer.

PSP 4’s PBI is just much smaller in scale than the others, so their offer is commensurately small, and is rejected on arrival. They are a little put off by the unceremonious rejection as they saw a great fit, and had moved quickly. The PBIs for 1 and 3 are relatively close in size. With a push PSP 3 elevates their initial proposal to 25% higher than where PSP 1 is willing to go.

PSP 3 is the top bidder by a good margin. You let PSP 1 know that you’re going a different direction and sign a term sheet with a 90 day exclusive period with PSP 3.

But the shade of PSP 3’s PBI isn’t all that dark, they are still getting there on the PBI. In reality they aren’t very committed to this PBI, nor this acquisition, and they’re starting to think they overbid. They make a few attempts to re-trade on the agreed upon deal based on things they discover in due diligence, but it’s all too expensive and there are just too many parts of the PBI still to figure out. They give you a call, terminate the transaction, and release you from exclusivity.

You make a flurry of calls. PSP 1 has moved on to an alternate startup. No luck there. PSP 2 is still too early in their thinking. PSP 4 was a bad breakup, they were really into it, feel jilted, and don’t return your call.

No deal, burned bridges, and you might have actually helped the other startup you can’t stand get a deal done as the replacement to you with PSP 1!

The two fundamental flaws in the thinking here were:

1) Thinking that your red box was the part driving value, and that the value of that single box must be roughly equivalent to all parties. But it’s not the red box - it’s the purple boxes. You want to be valued on what you can do together with the PSP, not valued on what you’re worth alone.

2) A massive underestimation of how long it takes to develop a PBI. You need dark purple to pull off a startup acquisition. PBIs (particularly big ones) are complex and require an enormous amount of organization alignment, it’s rare you can rush out and find several of them already baked.

When can bidding wars make sense?