Urgency: Breaking it Down, So You Can Build It Up

You can calculate urgency, here’s the equation: Urgency = Direction % x (Reward / n x Risk)

If you haven’t already - get the second edition of the MBP here.

Startup founders have a tough time with other people’s lack of urgency. Why is everyone so slow? Can’t they see how important this is?

It comes up constantly, but what is urgency? How does it come into being? What does it take to create it? Let’s break it down so we can learn how to build it up.

Urgency = Direction % x (Reward / n x Risk)

That’s it, that’s the MBP urgency equation. As with all we do on MBP.co, we want to understand how this phenomenon works so that we can turn things in our favor.

Let’s get to it.

Urgency

The definition of urgency is typically some variant of what I found in the Cambridge online dictionary: the quality of being very important and needing attention immediately. I asked ChatGPT to define urgency and this is what I got: Urgency is the quality or condition of requiring immediate attention or action due to its importance or time sensitivity. It often arises in situations where delays could lead to negative consequences, increased risks, or lost opportunities. Urgency can be driven by external deadlines, critical needs, or a sense of pressure to act quickly.

So for something to be urgent it has to be important, and it also must require immediate action. What I like about the ChatGPT definition of urgency is it begins to speak to the consequences of urgency (increased risks, lost opportunities) and the drivers (external deadlines, critical needs). If we want to create it, then we need to understand what it’s made of.

I would add to these definitions that urgency means the state of being where someone acts with greater speed than they normally would. It’s important to remember that people get all kinds of not particularly urgent things done. They just get them done slowly. A lack of urgency doesn’t mean something will never get done, it just means it isn’t going to get done very quickly. Urgency translates to speed. What we are trying to do when creating urgency is to increase the speed at which something is going to get done.

For MBP purposes, we’re talking about understanding, and potentially increasing, the speed at which a potential strategic partner (“PSP”) is advancing an opportunity.

Direction %

The dictionary definitions of urgency give us a hazy understanding of what’s going on, but they’re frankly a bit muddled and murky. To turn knowledge into action we need greater specificity as to the underlying dynamics. The first variable in the MBP urgency equation is Direction %. 100% being perfect directional alignment.

PSP Strategic Direction

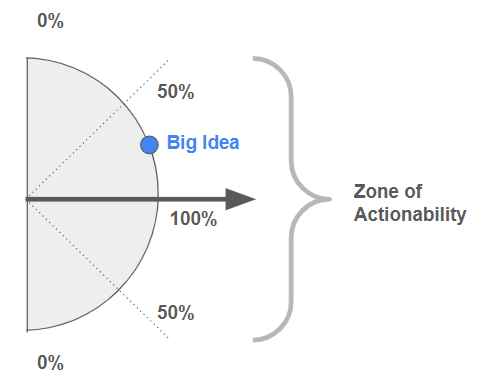

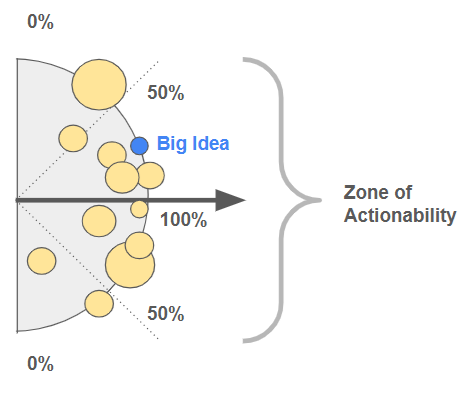

The PSP has a conceptualization of where it is going. A set of critical priorities, and how best to achieve them. For each PSP there’s a Zone of Actionability. This zone is the area within the outer bounds of the degrees of alignment required for an idea to be potentially acted upon. Some PSPs are entrepreneurial, innovative, and aggressive and their Zone of Actionability can be quite wide. For others who are very conservative the zone will be very narrow. So in understanding Direction % you’re both trying to understand how close this big idea is to perfect directional alignment, and also get a sense for how wide this particular PSP’s Zone of Actionability is.

But there’s one more thing to understand about Direction % and the Zone of Actionability: they’re moveable. The big idea and the PSP’s strategic direction affect each other. The big idea may actually change the PSP’s strategic direction, and the strategic direction may impact the big idea. The two aren’t static, but constantly evolving and adjusting - and it’s possible that they both move. Maybe they move closer together and create perfect alignment, or maybe new forces emerge that move them further apart.

Don’t underestimate the gravitational pull of a big idea, but also don’t underestimate the importance of the alignment of the big idea to the PSP’s strategic direction - PSP inertia isn’t something to be taken lightly! The big idea doesn’t exist in open space, it exists in the context of the PSP’s priorities.

Competition of ideas

In addition to existing in the context of the PSP’s priorities, the big idea also exists in relation to other competing ideas. PSP executive teams are most assuredly going to do something, at some point (they are paid to do stuff!). In fact, they will likely do many things. The question is will any of them be with you. The power of understanding urgency is in having a framework for increasing your urgency score - and in doing so - out-competing the other ideas upon which they could act.

Create the urgency required to knock the other ideas out of the way by aligning with Direction %, increasing the size of the Reward numerator, and decreasing the size of the n x Risk denominator.

Reward

The Magic Box Paradigm book is in large part a treatise on the Reward part of the equation. The Partner Big Idea (“PBI”) buildup is the development of the potential gain to be had by the PSP. As a practical guide to building Reward read the three part series on building a PBI (part 1, part 2, part 3). What I’ll add here to the topic of Reward is that it’s ultimately going to be heavily modified by the Direction %. So the stronger the alignment of the PBI is with the core direction of the PSP, the greater the amount of Urgency. As you’re building the PBI continue to work to understand the PSP’s driving priorities. It may be that the PBI is creating enough gravity to pull those priorities towards it, or it may be that you need to help adapt the PBI to better track to a set of priorities that are firmly positioned. What you don’t want is to have a PBI that exists detached from the ultimate direction the PSP is heading.

n x Risk

n is the degree of risk aversion for the PSP. This element has a multiplier effect on the amount of Risk the PSP anticipates it will take in pursuing the big idea. For example if Reward = 10 and Risk = 1, but the PSP is highly risk averse and has an n of 10 then the calculation is 10 / 10 x 1 (with the next effect being 10/10, or “1”) so even a 10x Reward return over the Risk of 1, is in fact only perceived to be even when you account for the intensely risk averse nature of the PSP.

Risk is the headwind pushing against the tailwind of the PBI. And the Risk headwind can be so powerful that it brings the PBI to a complete halt. To understand Risk we need to both develop a sense of the risk appetite of the PSP (what’s their “n” value?), as well as quantify the actual amount of Risk they would be taking in pursuit of this PBI. It might be tempting to focus the PBI conversation solely on Reward, but there’s a very good chance that the lurking monster of Risk will rise up and crush the PBI before it becomes reality.

Just as it’s safe to assume most PSPs won’t be experienced in developing full fledged PBIs, it’s just as safe to assume they aren’t great at calculating the risk of a bold new venture (often over estimating vs underestimating Risk). So you’ll likely have to help them develop a framework for considering the actual risks the venture poses. Naturally the contributing elements to Risk are going to be contextual to the situation at hand. But some things to consider are the cost to launch and operate the business line, the cost to acquire or partner with your startup, the opportunity cost of pursuing this big idea vs. alternatives, regulatory exposure, management distraction, and so on…

Once you (and the PSP) have a sense for baseline risk dynamics you’ll want to incorporate ways to de-risk the big idea. How can you show that this effort has all the earmarks of success? Customer demand is there, product launch (and market fit) and clearly achievable, distribution channels are primed, monetization is realistic. What are the areas that the PSP sees as most risky and how can you counteract those risks? De-risking will positively impact both the “n” value for risk aversion, and the aggregate value of the Risk itself.

Expanding on the PBI buildup in the MBP book, I’d add elements to the Methodology and Execution layers of the PBI that anticipate and de-risk the strategy. Get in front of the dynamics that will start to raise the larger risks and show how they can be accounted for through a well considered Method, and a thoughtful Execution plan.

Running the urgency calculation

Let’s run through an example.

Say at this moment the PBI that the PSP and you have created is about 75% aligned with their Direction, it has about 1,000 points of Reward, their organization has a medium level of risk aversion, so n=5 and the Risk of this strategy is around 100 points.

Urgency = 75% x (1,000 / 5 x 100)

Urgency = 1.5

The alternate project they are considering has 90% alignment with direction, but a smaller Reward of only 400 and much smaller Risk of just 10. It’s not nearly as big an idea, but it’s better aligned with Direction and way less risky.

Urgency = 90% x (400 / 5 x 10)

Urgency = 7.2

And pow, it’s got a MUCH higher urgency score. 7.2 for the smaller idea vs 1.5 for the big idea. Like it or not, when building PBIs with PSPs this is ultimately the calculation they are running. When you wonder why they aren’t moving faster, it’s because you aren’t aligned closely enough with their Direction, the Reward isn’t big enough, or there is just way too risk averse relative to the Risk they would have to take. If you want them to move faster, you’re going to need to change their inputs to this calculation.

Attention vs. urgency

There’s a secondary dictionary definition of urgency that’s important to understand: an earnest and insistent need. This definition of urgency has a durable quality. A need that is earnest and insistent isn’t simply going to go away. It has deep roots and is going to require attention. Most folks seriously misunderstand this deep and enduring aspect of urgency.

Many people mistake getting attention for creating urgency. There are levers you can pull to attract attention. For example by running a time limited process, or leveraging the FOMO that an opportunity is going to be gone if one doesn’t act now. In these cases attention and urgency are so close together they can become almost indistinguishable. However, as a transaction increases in complexity so does the gap between attention and urgency.

Say you’re a car dealer and you’re running a 4th of July sale. You get the customers attention with the sale banner, and you’re able to leverage the short duration of the sale period to create sufficient urgency to close the sale. Attention and urgency are almost indistinguishable. Now say you’re a startup and you leverage some exogenous force to compel a PSP to notice you. There’s a good chance you’ll get their attention. However, a startup M&A transaction is at least 1,000 times more complicated than, say, buying a car (and 1,000 times more complicated is probably a massive understatement). It’s not going to take a couple hours to get this deal done, it’s going to take months. You may get their attention based on their fear of missing a good deal, or losing an opportunity to a competitor, but if you don’t quickly leverage that attention to uncover an earnest and insistent need then their attention will quickly wear off, and their urgency will evaporate. In startup M&A getting attention and creating urgency aren’t the same, and you’ll want to make sure you mind the gap.

Risk Inversion

Pretty much every business opportunity exists within the constraints of the Urgency = Direction % x (Reward / n x Risk) calculation. However, some startups have a superpower that can transcend this calculation and fundamentally change the entire urgency game in their favor. They can change the calculation in such a massive way that the PSP’s urgency score explodes through a process I call: Risk Inversion.